Wāhanga Tuaiwa - Chapter Nine:

‘THE GREAT GREENSTONE TRIAL OF 1866’

In the story of Poutini’s Shore, the convergence of gold and greenstone would seem as inevitable as the tide. Wherever there are legends of treasure, human desire will follow and human nature will reveal. In January 1864, Simon the Maori strikes payable gold beneath a pounamu boulder in the Hohonu river, a tributary of the Taramakau that rises in the Hohonu Range above the southern

shore of Lake Brunner.

Haimona Tuakau - ‘Simon the Maori’ - Haimona Tuangau, all one and the same man of unique and singular character, his reputation as ‘the hardest working and most useful man in Westland’ was already well established by the advent of the West Coast gold rush brought about in no small part by his own discovery on the Hohonu. According to Mr J C Revell of the Canterbury Provincial Government office in Greymouth, it is also noted that ‘Simon brought over from Christchurch via Harpers Pass to Mawhera on February 11th, 1864, the first two horses to come to that district…’ I can find no other reference to this remarkable moment of pioneering enterprise but I’d bet all the amalgam in my only piece of bling, a pennyweight at least, that they were two pack horses purchased with his find, to help him haul out the real treasure, a great slab of pounamu that once nestled in the Hohonu on a little pile of gold.

Prospectors had been washing colour on the West Coast of South Island, then called West Canterbury, since the late 1850s, but colour in the pan alone does not make a gold rush. Worth anything from £2 to £4 an ounce in the 1860s, payable gold meant the ‘digger’ still came out ahead after the usual expenses had been deducted i.e. food, transport, accomodation and stores, which more often than not would include a healthy supply of grog, deemed an essential tonic of the soul for many a hardy pioneer adventurer to ‘the poor man’s diggings’. And pioneers they were, the diggers who made there way to Hokitika, Charleston, Waimangaroa, The Mokihinui, The Taramakau, The Berlins and Lyell on the Buller, and other momentary places that played out fast or never got going or promised just enough to drive a man drunk and ruin him.

The prospector Albert Hunt is one of the diggers credited with sparking the rush to the coast, apparently with a 20 oz find in the Hohonu, also called the Greenstone river, sometime between April and July 1864, so naming the goldfield there as the Hohonu Greenstone field. It is almost certain that Haimona Tuangau was the man who pointed Hunt in that particular direction. Hunt knew Tuangau from his time spent waylaid and frustrated at Mawhera Pa around May 1864, urgent in his quest to strike it rich and claim the £1000 prize offered by the Canterbury Provincial Council for finding payable gold in West Canterbury. Tuangau lived at Mawhera but also had a whare in the Taramakau, near the Hohonu, where he and his friend Samuel Iwikau te Aika often prospected. It is known that Hunt travelled down to the Hohonu with the two Maori prospectors around this time.

History seems a little uncertain about Albert Hunt, by turns generous or scathing as hero or hoaxer, with William Smart, another prospector who found his way to the Hohonu Greenstone at the same time, accusing Hunt of outright deception in his attempt to claim the Provincial Council prize. But diggers would soon descend on the Hohonu Greenstone field once Hunt and Smart put the word out. By February of 1865 the West Coast rush was on with news in the Christchurch Press that some 2375 ounces of gold had lately been shipped from ‘Okitika’. By the end of 1866 over half a million ounces of gold had been extracted from the alluvial fields of the west, and the town of Hokitika was booming.

Around December 1865 another prospector, James Reynolds, was on the Hohonu river seeking his fortune in both gold and greenstone, which you’d have to say is a sound business model given terrain of such fortunate geology, when he came across a large slab of pounamu in the bush quite near the stream at a place now called Maori Point if you look at a map of the area. The pounamu had clearly been placed there, and appeared to have been worked at over time, though perhaps not recently. Reynolds then regarded the pounamu slab as an abandoned ‘claim’ and staked it out as the Goldfields Act allowed of any abandoned ‘claim’ on a government declared goldfield.

Remembering Haimona Tuangau’s original find of ‘payable gold beneath a pounamu boulder’, we now return for a moment to January 1864 and the circumstances of ’Simon the Maori’s’ discovery. William Martin, a friend of Haimona Tuangau, himself a prospector in the Hohonu in 1863, lately a carpenter and bailiff in Christchurch, gives this account, having offered Tuangau a finders fee of £50 if he could locate any payable gold:

‘January 1864, his mate, Samuel (a Maori) [Iwikau] and himself [Tuakau] went up the Hohuna River, and on its main branch (the Greenstone Creek) they found an embedded boulder of pure greenstone, which, with the aid of levers cut in the bush, they eventually rolled out of it’s deep bed in the stream, and by rolling with the fall of the creek, placed the boulder in the bush out of sight and floods. An hour or two afterwards they went to the spot where the boulder had lain, with the discoloured water away, and on the side and bottom, embedded in the debris, they clearly saw shining in the clear water lumps of gold from one pennyweight to four or five, and, to use Simon’s own words, he said: ‘We take out our sheath knives and we take all we see, and I say to Samuel we want big hammer to break up the greenstone, and I say we no tell we find gold, but we go make a walk to Christchurch. We find Martina, get £50, buy big spawl hammer, bring Martina back with us, when we then tell all the Maoris, and all the Maoris go with us, get plenty of gold, we go to Christchurch and speak to many mans, but no one knows you. We make a walk about all day and see many men making the house, but we no see you working. We get very tired, buy a hammer, and go back to Kaiapoi, then we come home’.

Haimona Tuangau’s interest in gold, it seems to me, was pragmatic. His interest in pounamu came from a different deeper place. William Martin’s account shows us something, it shows us that Tuangau had exercised a claim of ownership over the greenstone boulder, evident by his actions, and therein exists a property right. Importantly, that right is one of custom, of tradition. It is a Maori right and it is permanent. The great greenstone trial of 1866 will decide if the Maori right has any standing in law because the greenstone slab found and claimed by Reynolds was the same pounamu boulder put there by Haimona Tuangau when he found his gold.

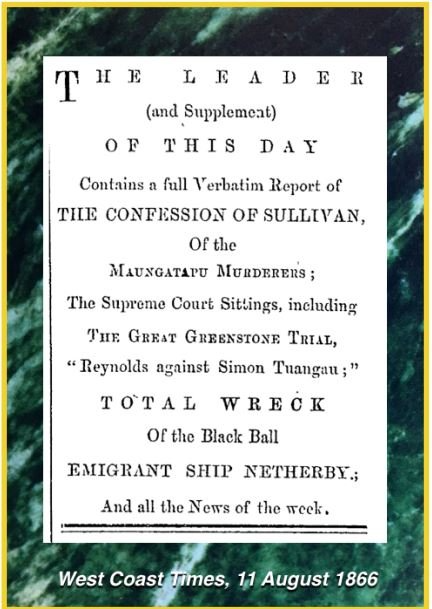

Subsequent to staking out the pounamu boulder another Pākeha on the Hohonu, Bill Chappell, informed Reynolds that he had no claim on it, that in fact he (Chappell) was ‘looking after the boulder for the Maoris’. Mr Revell, the Warden at Greymouth would later support this view; ‘The stone you have taken possession of belongs to Simon Tuangau and I think you had better not touch it’. Revell was of the opinion that because Tuangau found the boulder before the Goldfields Act applied in the Hohonu Greenstone field, the issue was one of property, not a mining claim. Reynolds approached Tuangau directly, looking for a deal. Tuangau declined. Reynolds brought explosives to the site and broke up the boulder yielding nearly 1900 pounds of pounamu worth an estimated £2500, roughly equivalent to around 1000 ounces of gold. Tuangau slapped a writ on Reynolds, and police seized the pounamu on the authority of a warrant issued by the resident magistrate at Greymouth. Reynolds brought his own action against Tuangau alleging unlawful detention of the greenstone and commencing criminal proceedings. The case went to the Supreme Court in Hokitika and then in August 1866, after two juries failed to reach agreement, was referred by the presiding Judge on a point of law to the Court of Appeal in Wellington.

In the event, the Court of Appeal ruled in favour of Tuangau, accepting the argument that a traditional property right predated goldfield regulations. Haimona Tuangau was able to show he had asserted that right. Werita Tainui, a Ngāti Waewae Rangatira testified, in Maori, that ‘Simon’ had asked him to break pieces from the stone soon after it was found and that under native law, the stone belonged to Tuangau, even if left unattended for long periods. Revell as well, also gave evidence in support of Tuangau. In October 1866 the Court of Appeal, in a unanimous decision, found that a property right based on custom and tradition lay with Haimona ‘Simon’ Tuangau, a Maori, and awarded him costs.

Epilogue:

Haimona Tuakau - ‘Simon the Maori’ - Haimona Tuangau, all one and the same man of unique and singular character, his reputation as ‘the hardest working and most useful man in Westland’ was already well established by the advent of the West Coast gold rush brought about in no small part by his own discovery on the Hohonu. According to Mr J C Revell of the Canterbury Provincial Government office in Greymouth, it is also noted that ‘Simon brought over from Christchurch via Harpers Pass to Mawhera on February 11th, 1864, the first two horses to come to that district…’ I can find no other reference to this remarkable moment of pioneering enterprise but I’d bet all the amalgam in my only piece of bling, a pennyweight at least, that they were two pack horses purchased with his find, to help him haul out the real treasure, a great slab of pounamu that once nestled in the Hohonu on a little pile of gold.

Prospectors had been washing colour on the West Coast of South Island, then called West Canterbury, since the late 1850s, but colour in the pan alone does not make a gold rush. Worth anything from £2 to £4 an ounce in the 1860s, payable gold meant the ‘digger’ still came out ahead after the usual expenses had been deducted i.e. food, transport, accomodation and stores, which more often than not would include a healthy supply of grog, deemed an essential tonic of the soul for many a hardy pioneer adventurer to ‘the poor man’s diggings’. And pioneers they were, the diggers who made there way to Hokitika, Charleston, Waimangaroa, The Mokihinui, The Taramakau, The Berlins and Lyell on the Buller, and other momentary places that played out fast or never got going or promised just enough to drive a man drunk and ruin him.

The prospector Albert Hunt is one of the diggers credited with sparking the rush to the coast, apparently with a 20 oz find in the Hohonu, also called the Greenstone river, sometime between April and July 1864, so naming the goldfield there as the Hohonu Greenstone field. It is almost certain that Haimona Tuangau was the man who pointed Hunt in that particular direction. Hunt knew Tuangau from his time spent waylaid and frustrated at Mawhera Pa around May 1864, urgent in his quest to strike it rich and claim the £1000 prize offered by the Canterbury Provincial Council for finding payable gold in West Canterbury. Tuangau lived at Mawhera but also had a whare in the Taramakau, near the Hohonu, where he and his friend Samuel Iwikau te Aika often prospected. It is known that Hunt travelled down to the Hohonu with the two Maori prospectors around this time.

History seems a little uncertain about Albert Hunt, by turns generous or scathing as hero or hoaxer, with William Smart, another prospector who found his way to the Hohonu Greenstone at the same time, accusing Hunt of outright deception in his attempt to claim the Provincial Council prize. But diggers would soon descend on the Hohonu Greenstone field once Hunt and Smart put the word out. By February of 1865 the West Coast rush was on with news in the Christchurch Press that some 2375 ounces of gold had lately been shipped from ‘Okitika’. By the end of 1866 over half a million ounces of gold had been extracted from the alluvial fields of the west, and the town of Hokitika was booming.

Around December 1865 another prospector, James Reynolds, was on the Hohonu river seeking his fortune in both gold and greenstone, which you’d have to say is a sound business model given terrain of such fortunate geology, when he came across a large slab of pounamu in the bush quite near the stream at a place now called Maori Point if you look at a map of the area. The pounamu had clearly been placed there, and appeared to have been worked at over time, though perhaps not recently. Reynolds then regarded the pounamu slab as an abandoned ‘claim’ and staked it out as the Goldfields Act allowed of any abandoned ‘claim’ on a government declared goldfield.

Remembering Haimona Tuangau’s original find of ‘payable gold beneath a pounamu boulder’, we now return for a moment to January 1864 and the circumstances of ’Simon the Maori’s’ discovery. William Martin, a friend of Haimona Tuangau, himself a prospector in the Hohonu in 1863, lately a carpenter and bailiff in Christchurch, gives this account, having offered Tuangau a finders fee of £50 if he could locate any payable gold:

‘January 1864, his mate, Samuel (a Maori) [Iwikau] and himself [Tuakau] went up the Hohuna River, and on its main branch (the Greenstone Creek) they found an embedded boulder of pure greenstone, which, with the aid of levers cut in the bush, they eventually rolled out of it’s deep bed in the stream, and by rolling with the fall of the creek, placed the boulder in the bush out of sight and floods. An hour or two afterwards they went to the spot where the boulder had lain, with the discoloured water away, and on the side and bottom, embedded in the debris, they clearly saw shining in the clear water lumps of gold from one pennyweight to four or five, and, to use Simon’s own words, he said: ‘We take out our sheath knives and we take all we see, and I say to Samuel we want big hammer to break up the greenstone, and I say we no tell we find gold, but we go make a walk to Christchurch. We find Martina, get £50, buy big spawl hammer, bring Martina back with us, when we then tell all the Maoris, and all the Maoris go with us, get plenty of gold, we go to Christchurch and speak to many mans, but no one knows you. We make a walk about all day and see many men making the house, but we no see you working. We get very tired, buy a hammer, and go back to Kaiapoi, then we come home’.

Haimona Tuangau’s interest in gold, it seems to me, was pragmatic. His interest in pounamu came from a different deeper place. William Martin’s account shows us something, it shows us that Tuangau had exercised a claim of ownership over the greenstone boulder, evident by his actions, and therein exists a property right. Importantly, that right is one of custom, of tradition. It is a Maori right and it is permanent. The great greenstone trial of 1866 will decide if the Maori right has any standing in law because the greenstone slab found and claimed by Reynolds was the same pounamu boulder put there by Haimona Tuangau when he found his gold.

Subsequent to staking out the pounamu boulder another Pākeha on the Hohonu, Bill Chappell, informed Reynolds that he had no claim on it, that in fact he (Chappell) was ‘looking after the boulder for the Maoris’. Mr Revell, the Warden at Greymouth would later support this view; ‘The stone you have taken possession of belongs to Simon Tuangau and I think you had better not touch it’. Revell was of the opinion that because Tuangau found the boulder before the Goldfields Act applied in the Hohonu Greenstone field, the issue was one of property, not a mining claim. Reynolds approached Tuangau directly, looking for a deal. Tuangau declined. Reynolds brought explosives to the site and broke up the boulder yielding nearly 1900 pounds of pounamu worth an estimated £2500, roughly equivalent to around 1000 ounces of gold. Tuangau slapped a writ on Reynolds, and police seized the pounamu on the authority of a warrant issued by the resident magistrate at Greymouth. Reynolds brought his own action against Tuangau alleging unlawful detention of the greenstone and commencing criminal proceedings. The case went to the Supreme Court in Hokitika and then in August 1866, after two juries failed to reach agreement, was referred by the presiding Judge on a point of law to the Court of Appeal in Wellington.

In the event, the Court of Appeal ruled in favour of Tuangau, accepting the argument that a traditional property right predated goldfield regulations. Haimona Tuangau was able to show he had asserted that right. Werita Tainui, a Ngāti Waewae Rangatira testified, in Maori, that ‘Simon’ had asked him to break pieces from the stone soon after it was found and that under native law, the stone belonged to Tuangau, even if left unattended for long periods. Revell as well, also gave evidence in support of Tuangau. In October 1866 the Court of Appeal, in a unanimous decision, found that a property right based on custom and tradition lay with Haimona ‘Simon’ Tuangau, a Maori, and awarded him costs.

Epilogue:

Above is a letter written in Māori by Haimona Tuangau in 1866, from ‘Hokitika ki toku hoa aroha, ki a te Kawana’ - from Hokitika, to my dear friend, the Governor, being Governor George Grey. The letter acknowledges the Governor’s kindness in sending him a gift of preserved birds on the steamer but regrets that he cannot show him due consideration because the Pākeha have stolen his horses and he is poor at the moment. He states that goods have been stolen from him four times in four and a half years of living i tenei whenua - in this place. Tuangau then offers a small token of friendship, he pounamu - a piece of greenstone weighing about 44’ (possibly 44 pennyweight or just under 2.5 troy ounces, being standard weight measures for gold). He finishes the letter; ‘My friend, I have not seen a bird for you yet so I can’t come there to see you and Te Rauparaha. I don’t have enough money to pay for me and my wife to come. And so then, from your dear friend, Haimona Tuangau.

Haimona Tuangau was born about 1840 in the Bay of Islands. As a boy he was kidnapped and taken aboard a whaler, a matter which was later said to be ‘settled’ with a keg of tobacco to the aggrieved hapu or tribal grouping. Some years later he jumped ship in Akaroa and was hidden by local Maori for a while, before heading for Te Tai a Poutini - West Coast, then called West Canterbury, with his wife Patahi, a Māori woman from Otakau (Otago). He is very much a transitional character in the narrative of New Zealand, forging his own place in the evolving milieu through intelligence, hard work, strength of character and an instinctive awareness that the world was changing irrevocably. Tuangau lived that change. Through him tradition and custom found acknowledgement in law. He died in 1890. Too young.

Haimona Tuangau was born about 1840 in the Bay of Islands. As a boy he was kidnapped and taken aboard a whaler, a matter which was later said to be ‘settled’ with a keg of tobacco to the aggrieved hapu or tribal grouping. Some years later he jumped ship in Akaroa and was hidden by local Maori for a while, before heading for Te Tai a Poutini - West Coast, then called West Canterbury, with his wife Patahi, a Māori woman from Otakau (Otago). He is very much a transitional character in the narrative of New Zealand, forging his own place in the evolving milieu through intelligence, hard work, strength of character and an instinctive awareness that the world was changing irrevocably. Tuangau lived that change. Through him tradition and custom found acknowledgement in law. He died in 1890. Too young.

References:

Austin, Dougal. Hei Tiki: He Whakamārama Hōu. MA thesis in Māori Studies. Victoria University of Wellington. 2014.

Bradshaw, Julia. A Tiny Treasure. https://www.canterburymuseum.com/discover/blog-posts/a-tinytreasure/

Pickering, Mark. The Colours: The search for payable gold on the West Coast from 1857 to 1864. http://www.bestwalks.kiwi.nz/uploads/4/9/3/3/49336433/the_colours_new_design.pdf

Taylor, W. A. Lore and History of the South Island Maori. Bascands Limted, Christchurch. 1950.

Letter from Haimona Tuakau courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections GNZMA 306

Austin, Dougal. Hei Tiki: He Whakamārama Hōu. MA thesis in Māori Studies. Victoria University of Wellington. 2014.

Bradshaw, Julia. A Tiny Treasure. https://www.canterburymuseum.com/discover/blog-posts/a-tinytreasure/

Pickering, Mark. The Colours: The search for payable gold on the West Coast from 1857 to 1864. http://www.bestwalks.kiwi.nz/uploads/4/9/3/3/49336433/the_colours_new_design.pdf

Taylor, W. A. Lore and History of the South Island Maori. Bascands Limted, Christchurch. 1950.

Letter from Haimona Tuakau courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections GNZMA 306