Wāhanga Tuatekau - Chapter Ten:

KI NGĀ HAU E WHA I ATU RA TO THE FOUR WINDS AND BEYOND

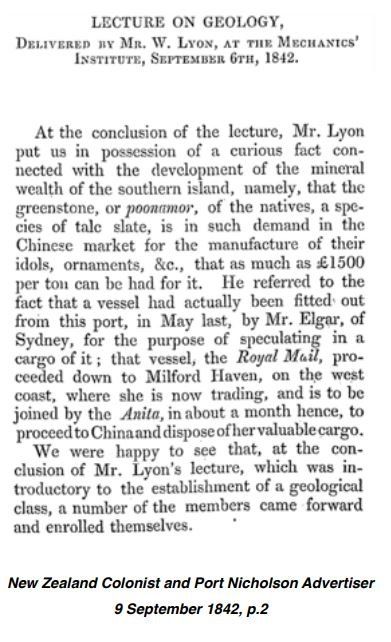

I can find no other record of the Orient adventure mentioned by Mr W Lyon in the closing remarks of his lecture on the various geological strata of New Zealand to the merchants of an aspirant young Wellington, though both the schooners ‘Royal Mail’ and ‘Anita’ plied these islands in the 1840s. These early days of Colony present both risk and opportunity to bold and entrepreneurial ship owners and masters. I can well imagine the idea of a couple of holds full of ‘New Zealand jade’ landed in Shanghai at £1500 a ton inspiring just such a speculative enterprise. There is a record of the ‘Anita’ arriving in Port Nicholson (Wellington) on Christmas Eve 1842 from Manilla so It’s certainly not beyond the realms of possibility that the crew of Anita made it back to New Zealand just in time for Christmas dinner, cashed up presumably, after a dash up to China with a hold full of Tangiwai, the bowenite lookalike to nephrite jade that Piopiotahi or ‘Milford Haven’ is known for when it comes to pounamu, technically speaking however, bowenite is not jade.

F or want of nothing more than a start date I’m going to assume that this was the first reported commercial, industrial scale international export of pounamu from Aotearoa. With that in mind, we can say that it was a business that lasted just over 100 years, 1842 - 1947, though the Milford - China run seems a one-off transaction in the record, albeit conceivably several hundred tons worth. Between 1842 and 1866 however, the record is more or less silent. I think it’s reasonable to assume that there will have been moments of opportunity in the interim, just as there was prior to 1842. Tucker the Sydney souvenir trader for example, the chancer whom we met in chapter five dying his death at Murdering Beach, Otago in 1817.

F or want of nothing more than a start date I’m going to assume that this was the first reported commercial, industrial scale international export of pounamu from Aotearoa. With that in mind, we can say that it was a business that lasted just over 100 years, 1842 - 1947, though the Milford - China run seems a one-off transaction in the record, albeit conceivably several hundred tons worth. Between 1842 and 1866 however, the record is more or less silent. I think it’s reasonable to assume that there will have been moments of opportunity in the interim, just as there was prior to 1842. Tucker the Sydney souvenir trader for example, the chancer whom we met in chapter five dying his death at Murdering Beach, Otago in 1817.

George Weller-Poley from Boxted Hall in Suffolk, England travelled down to New Zealand in the 1820s, returning home to his moated country manor house set in gloriously picturesque grounds near Bury St Edmunds, with a mokomokai - the preserved head of a Māori warrior - and the mere pounamu pictured here. But the gentleman adventurer wasn’t in it for profit. These were memories manifest of an exotic road less travelled, which he had no intention of selling. That would fall to his descendants. The mokomokai was offered for sale in 1988 but caused something of a stir. The remnant warrior was withdrawn from auction and eventually came home, exchanged in an expression of gratitude and good will for another mere pounamu, a modern reproduction. The older mere pounamu, George Weller-Poley’s memento, sold for £12,500 in June 2020. The reproduction gifted to the Weller-Poley family was also offered for sale at the same auction but failed to reach reserve and was passed in with a final bid of £3000.

It seems to me that some people have funny ideas about concepts like ‘propriety’, ‘value’ and ‘worth’, but that’s just my opinion. I can’t say I’m comfortable with old George Weller-Poley’s original ‘souveniring’ of taonga, but to be fair, there’s an even chance he would have traded for his goods with Māori, or just stumped up with the readies. Māori by then were not necessarily averse to either, so long as the barter had utility or there was something worth buying with the cash. Anyway, viewing 1820s actions through 2021 eyes is less than helpful sometimes, not always, but sometimes. Of his era and in his way, Weller-Poley expressed a measure of respect for these artefacts by keeping them as part of a cherished household collection. I’m not sure what to make of his descendants view on the matter though. It all feels a little bit, I don’t know, cheap and tacky somehow. But as I say, that’s just my opinion.

N ew lands in the cradle of Nationhood always attract adventurers and opportunists. Even pioneer settlers are speculators to some degree. Taking a chance on the unknown comes with the territory, literally. But the pioneer’s perception of a profitable outcome often looks less like money and more like a future filled with promise, although it’s always a bonus when one attends the other. The pioneer settlers that descended on Poutini’s shore from all around the world chasing riches in the gold rush of 1865 came clearly with profit in mind.

It seems to me that some people have funny ideas about concepts like ‘propriety’, ‘value’ and ‘worth’, but that’s just my opinion. I can’t say I’m comfortable with old George Weller-Poley’s original ‘souveniring’ of taonga, but to be fair, there’s an even chance he would have traded for his goods with Māori, or just stumped up with the readies. Māori by then were not necessarily averse to either, so long as the barter had utility or there was something worth buying with the cash. Anyway, viewing 1820s actions through 2021 eyes is less than helpful sometimes, not always, but sometimes. Of his era and in his way, Weller-Poley expressed a measure of respect for these artefacts by keeping them as part of a cherished household collection. I’m not sure what to make of his descendants view on the matter though. It all feels a little bit, I don’t know, cheap and tacky somehow. But as I say, that’s just my opinion.

N ew lands in the cradle of Nationhood always attract adventurers and opportunists. Even pioneer settlers are speculators to some degree. Taking a chance on the unknown comes with the territory, literally. But the pioneer’s perception of a profitable outcome often looks less like money and more like a future filled with promise, although it’s always a bonus when one attends the other. The pioneer settlers that descended on Poutini’s shore from all around the world chasing riches in the gold rush of 1865 came clearly with profit in mind.

Diggers dreamed the ends of rainbows, but mostly they just got rain. Merchants took stock of every make and manner working the margin with precision down to the nth of a pennyweights worth. Prostitutes prettied themselves and pretended. Bankers charged interest and collected or foreclosed. Thieves and deceivers thieved and deceived. Priests found new souls to pray for and hoteliers in their hundreds did a roaring trade supplying them, for a while anyway. Meanwhile, Māori looked around and wondered what exactly happened.

In Hokitika, German businessman Joseph Klein opened a jeweller tobacconist premises on Revell Street in 1865. He was also the owner of the West Coast Times which advertised a range of greenstone jewellery in 1868 newly arrived in the colony from far off Idar-Oberstein, a twin town settlement on the Nahe river in Germany, where his brother Karl worked as a lapidary in the 400 year old gemstone industry centred there. Agate had been mined in the surrounding countryside since the 1400s, utilising the Nahe - a tributary of the Rhine - to power the mills and grinding stones. By the 1800s the agate fields were all but mined out so the industry cast further afield to the new world, and Idar-Oberstein kept going. ’GREENSTONE PENDANTS, PINS, EAR-RINGS &c.’ were now on display and available at J.P. Klein’s on Revell Street. The ‘GREENSTONE’ was pounamu all the way from here.

It would seem an historical inevitability that a commercial greenstone trade should emerge from tailings of the West Coast rush and the happy geological coincidence of gold awash in rivers of greenstone. But from the mid 1860s, jewellers and lapidaries began working with the local resource in earnest. Very soon a distinct Victorian colonial aesthetic began to appear in the windows and display cases of jewellery shops from Dunedin to Auckland. Kia Ora, Aroha, Aotearoa appeared in delicately cursive gold or silver on pendants and brooches of pounamu hung from finely wrought chains or framed in elaborate filigrees. Ake Ake Ake, spelling ‘forever’ in gold on greenstone cut and set in a classic jewellery motif suggests to me aspirations of permanence and a feeling of confidence in this far flung corner of Empire. Interestingly, it also reveals a readiness among the colonists to express some kind of indigenous context to an emerging sense of national identity. Ironically however, the greenstone rush that began in the mid 1860s saw most of the vast tonnage of pounamu extracted from the West Coast riverine being loaded onto ships and sent off to the industrialised workshops of Germany and England, part of a circular trade that would last until the second world war.

References: Street, Kathryn. The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860s - 1940s. Victoria University of Wellington, MA (History) 2014

George Weller-Poley mere and information: https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/print-edition/2020/july/2452/auction-reports/maorigreenstone-brought-to-britain-by-1820s-adventurer/

For all historical News Paper references: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz

In Hokitika, German businessman Joseph Klein opened a jeweller tobacconist premises on Revell Street in 1865. He was also the owner of the West Coast Times which advertised a range of greenstone jewellery in 1868 newly arrived in the colony from far off Idar-Oberstein, a twin town settlement on the Nahe river in Germany, where his brother Karl worked as a lapidary in the 400 year old gemstone industry centred there. Agate had been mined in the surrounding countryside since the 1400s, utilising the Nahe - a tributary of the Rhine - to power the mills and grinding stones. By the 1800s the agate fields were all but mined out so the industry cast further afield to the new world, and Idar-Oberstein kept going. ’GREENSTONE PENDANTS, PINS, EAR-RINGS &c.’ were now on display and available at J.P. Klein’s on Revell Street. The ‘GREENSTONE’ was pounamu all the way from here.

It would seem an historical inevitability that a commercial greenstone trade should emerge from tailings of the West Coast rush and the happy geological coincidence of gold awash in rivers of greenstone. But from the mid 1860s, jewellers and lapidaries began working with the local resource in earnest. Very soon a distinct Victorian colonial aesthetic began to appear in the windows and display cases of jewellery shops from Dunedin to Auckland. Kia Ora, Aroha, Aotearoa appeared in delicately cursive gold or silver on pendants and brooches of pounamu hung from finely wrought chains or framed in elaborate filigrees. Ake Ake Ake, spelling ‘forever’ in gold on greenstone cut and set in a classic jewellery motif suggests to me aspirations of permanence and a feeling of confidence in this far flung corner of Empire. Interestingly, it also reveals a readiness among the colonists to express some kind of indigenous context to an emerging sense of national identity. Ironically however, the greenstone rush that began in the mid 1860s saw most of the vast tonnage of pounamu extracted from the West Coast riverine being loaded onto ships and sent off to the industrialised workshops of Germany and England, part of a circular trade that would last until the second world war.

References: Street, Kathryn. The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860s - 1940s. Victoria University of Wellington, MA (History) 2014

George Weller-Poley mere and information: https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/print-edition/2020/july/2452/auction-reports/maorigreenstone-brought-to-britain-by-1820s-adventurer/

For all historical News Paper references: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz