Wāhanga Tuawha: Chapter Four

E hara! He mata toki onewa hapurupuru mārire, kāpātaua he mata toki pounamu, e tū te tātai o te whakairo. A blade of common stone cannot fall gracefully, only a pounamu blade can smooth the carving.

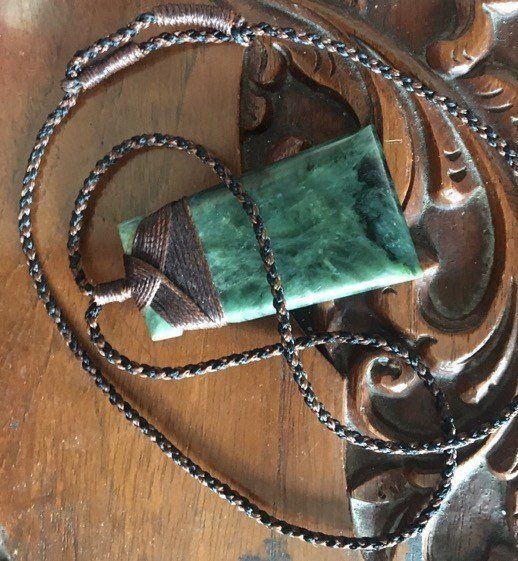

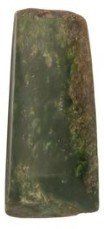

This image is my toki. It represents the blade of an adze. It measures approximately 2.5 cm wide at the sharp end tapering to about 2 cm at the shoulder along a length of 5 cm. Someone dear to me gave it as a Christmas present in 2019. She asked Hohepa Bowen, whom we met in chapter two, to make one especially for me

Hohepa bound it as well. Just as he is in the working of stone, he is very particular about binding. In the old days such methods of binding made for a firm attachment to the kakau toki - the haft of the adze. Strictly speaking, we would call this a hei toki, that is,

a toki to be worn around the neck. As a piece of personal ornamentation the hei toki brings with it story, tradition and meaning. It is worn to be shown, not hidden. It is a statement piece. It reveals intention and spirit.

The toki is also a karakia, or incantation, that addresses a tree to be felled during the kawa, when the ceremonial toki poutangata is used to make the first symbolic blows, removing chips of wood from the tree and taking them to some secret place in the forest, there to be buried as an offering of thanks to Tane Mahuta and his mother Papatuānuku. Typically these trees will be used in the

building of wharenui and waka, or the carving of ancestral pou, work of great mana and tapu. How does a simple blade of stone age design become imbued with so much potency and presence?

According to the traditions, Te Awhiorangi - The embrace of the heavens - was the first tool, the first implement of utility, the blade that severed the bonds of darkness and later cleaved the waves allowing passage through the stormy seas from mythical Hawaiki. Stories from across the motu place this mighty toki in the hands of Tane Mahuta at the beginning of days. As with pounamu, stories of Te Awhiorangi abound and there are many traditions laying claim to the guardianship of this most tapu, this most sacred artefact.

The toki is also a karakia, or incantation, that addresses a tree to be felled during the kawa, when the ceremonial toki poutangata is used to make the first symbolic blows, removing chips of wood from the tree and taking them to some secret place in the forest, there to be buried as an offering of thanks to Tane Mahuta and his mother Papatuānuku. Typically these trees will be used in the

building of wharenui and waka, or the carving of ancestral pou, work of great mana and tapu. How does a simple blade of stone age design become imbued with so much potency and presence?

According to the traditions, Te Awhiorangi - The embrace of the heavens - was the first tool, the first implement of utility, the blade that severed the bonds of darkness and later cleaved the waves allowing passage through the stormy seas from mythical Hawaiki. Stories from across the motu place this mighty toki in the hands of Tane Mahuta at the beginning of days. As with pounamu, stories of Te Awhiorangi abound and there are many traditions laying claim to the guardianship of this most tapu, this most sacred artefact.

The two great competing claims of the Aotea and Takitimu tribal waka are probably the most well known across Te Ao Māori - The Māori World - but Te Awhiorangi has been linked to ancestors and waka throughout these islands, with each competing claim as adamant as the next to record that their own mana is inextricably linked to the magical blade, thereby ensuring a whakapapa of insurmountable greatness.

There is kōrero as well, emanating from old South Taranaki traditions, that mention Ngahue as both custodian and maker of Te Awhiorangi, asserting the toki was made of pounamu, and that it was Ngahue himself who gave it to Tane. You will recall from chapter three that Ngahue has strong

associations with both the discovery and working of pounamu. He is spoken of as a contemporary of Kupe, who is said to have found Aotearoa in the first place. I will say with respect to Kupe that there is another tradition, which tells us the great Polynesian navigator already knew of this land to the south and was following the wake of an earlier adventurer whom popular mythology now recalls as a Demi-god named Maui. But I will have that conversation another time within a more relevant context.

associations with both the discovery and working of pounamu. He is spoken of as a contemporary of Kupe, who is said to have found Aotearoa in the first place. I will say with respect to Kupe that there is another tradition, which tells us the great Polynesian navigator already knew of this land to the south and was following the wake of an earlier adventurer whom popular mythology now recalls as a Demi-god named Maui. But I will have that conversation another time within a more relevant context.

As to Ngahue, I can only speculate that his association with Te Awhiorangi is perhaps bound up with the firmly asserted traditions of the Aotea waka and its people, who settled in Taranaki. Ngahue has strong links with the Taranaki area as well. It seems he called it home, at least while he was here, for it is said he travelled back to Polynesia taking the pounamu with him.

In 1887 a deeply significant event occurred for the people of Aotea waka. An ancient artefact - a toki - was found concealed near a tapu burial cave not far from the small town of Waitotara in South Taranaki. As recorded by Elsdon Best in his book, The Stone Implements of The Māori (1912), the toki is described thus; “…a red-looking axe, the material looking something like china, and speckled like the bird pipiwharauroa. A person can see his face reflected in it. It is 1 ft. 6 in. long and 1 in. thick; the cutting-edge is 2 1/2 in.”

According to the local Ngā Rauru people, this toki was the adze of legend, Te Awhiorangi. Te Rangi Takoru, an authority of the day from Whangaehu, states that the toki was brought to Aotearoa by Turi, the captain of the Aotea. Te Rangi adds detail to the description of Te Awhiorangi. The handle (kakau) he names as Kawe-kai-rangi. The kaupare - a wooden wedge placed under the lashing - and the lashing itself, was named Pare-te-rangi and Whakakapua respectively. A chord connected with the shaft of the handle was call the kaha paepae.

In 1887 a deeply significant event occurred for the people of Aotea waka. An ancient artefact - a toki - was found concealed near a tapu burial cave not far from the small town of Waitotara in South Taranaki. As recorded by Elsdon Best in his book, The Stone Implements of The Māori (1912), the toki is described thus; “…a red-looking axe, the material looking something like china, and speckled like the bird pipiwharauroa. A person can see his face reflected in it. It is 1 ft. 6 in. long and 1 in. thick; the cutting-edge is 2 1/2 in.”

According to the local Ngā Rauru people, this toki was the adze of legend, Te Awhiorangi. Te Rangi Takoru, an authority of the day from Whangaehu, states that the toki was brought to Aotearoa by Turi, the captain of the Aotea. Te Rangi adds detail to the description of Te Awhiorangi. The handle (kakau) he names as Kawe-kai-rangi. The kaupare - a wooden wedge placed under the lashing - and the lashing itself, was named Pare-te-rangi and Whakakapua respectively. A chord connected with the shaft of the handle was call the kaha paepae.

Takitimu waka descendants have a different view of things. Their traditions says that the toki tapu or sacred adze was brought to Aotearoa with them and in fact was used by Tamatea, their famous captain, to cleave a way through a great storm sent to delay or even sink them. Later in Aotearoa the adze was given by Tamatea to the daughter of Turi of the Aotea, Tane-roa when she became wife to Uhenga-ariki, Tamatea’s brother. This, according to Takitimu, is how Te Awhiorangi came to be within the charge of the people of Taranaki.

Of course, pounamu was much favoured as a toki for its hardness and capacity to hold an edge. Greenstone chisels, or whao, must have have been highly prized as well by tohunga whakairo for the same reason, being ideally suited for finer detailed work. But surely the most sacred of toki would have been the toki poutangata, a ceremonial adze possessed only by Ariki or Tōhunga of great mana, such was the tapu of such these particular objects. Why? Because the toki gave a seafaring people the means build the great waka of ancestry and discovery and the great houses that sheltered the people.

The tool itself, such ancient technology, is barely used these days except in the hands of artisans, craftsmen and kaiwhakairo, now happy to wield in metal what once was made of stone, just as the

ancestors took up iron nails and chisels. But the basic design is unchanged in all these thousands of years. Once upon a time, using an adze was part of a job I had maintaining and repairing timber railway bridges. We shaped great logs of iron bark, red gum and jarrah to use as girders, headstocks, piers and transoms to carry the weight of the bridge and the trains that crossed over. Simple tools, pleasing to use and sufficient to the task until concrete and steel replaced the need to wield them.

The toki shows us that through appropriate use and proper conduct we can shape our world, exert authority, yield worth and value. We can sustain ourselves. The toki does what all good tools should do. It amplifies our strength, enhances our skills, increases our capacity to control our environment. Tools give us power over things. Used properly and with due consideration of the consequences, great benefits flow and we are advanced in some way. Tools give us mana. Mastery of the toki by the ancestors allowed them their greatest endeavours. These are the aspects that emanate from the toki motif. When rendered in pounamu, the mana of the toki is manifold and immense. The glory of the stone, the power of the blade, this is what hangs from my neck.

ancestors took up iron nails and chisels. But the basic design is unchanged in all these thousands of years. Once upon a time, using an adze was part of a job I had maintaining and repairing timber railway bridges. We shaped great logs of iron bark, red gum and jarrah to use as girders, headstocks, piers and transoms to carry the weight of the bridge and the trains that crossed over. Simple tools, pleasing to use and sufficient to the task until concrete and steel replaced the need to wield them.

The toki shows us that through appropriate use and proper conduct we can shape our world, exert authority, yield worth and value. We can sustain ourselves. The toki does what all good tools should do. It amplifies our strength, enhances our skills, increases our capacity to control our environment. Tools give us power over things. Used properly and with due consideration of the consequences, great benefits flow and we are advanced in some way. Tools give us mana. Mastery of the toki by the ancestors allowed them their greatest endeavours. These are the aspects that emanate from the toki motif. When rendered in pounamu, the mana of the toki is manifold and immense. The glory of the stone, the power of the blade, this is what hangs from my neck.

Glossary:

Aotea: Ancestral waka. Ariki: Paramount chief. Kaiwhakairo: Carver.

Karakia: Prayer, chant, incantation.

Kawa: Ceremonies of importance. Etiquette.

Kōrero: Talk, conversation, story.

Kupe: According to our popular mythology, the discoverer of Aotearoa.

Maui: Mythical figure; a demi God.

Motu: Island, sometimes used as a generic term for ‘this place’. Papatuānuku: The earth, primordial and mythological mother. Pipiwharauroa: Shining cuckoo. Pou: A post. To establish, erect, support. Stalwart.

Takitimu: Ancestral waka.

Tane Mahuta: Deity of humankind, forests, birds and creatures therein.

Tohunga whakairo: Expert carver.

Waka: A canoe. Ocean going craft of ancestry.

Wharenui: Literally ‘great house’. The ancestral house on the marae.

Kawa: Ceremonies of importance. Etiquette.

Kōrero: Talk, conversation, story.

Kupe: According to our popular mythology, the discoverer of Aotearoa.

Maui: Mythical figure; a demi God.

Motu: Island, sometimes used as a generic term for ‘this place’. Papatuānuku: The earth, primordial and mythological mother. Pipiwharauroa: Shining cuckoo. Pou: A post. To establish, erect, support. Stalwart.

Takitimu: Ancestral waka.

Tane Mahuta: Deity of humankind, forests, birds and creatures therein.

Tohunga whakairo: Expert carver.

Waka: A canoe. Ocean going craft of ancestry.

Wharenui: Literally ‘great house’. The ancestral house on the marae.