Wāhanga Waru. Chapter Eight

The Blessed Stone A personal observation

On the question of whether or not to bless the greenstone - ka whakatapu te pounamu - you must first ask yourself the bigger question, ‘What do I believe?’ Hold that thought for a while, and let’s consider context. Today in Aotearoa New Zealand I think most of us would agree that pounamu, or greenstone if you like, is, for want of a better term, our national stone. We regard it as taonga, a treasure. We can imagine that it somehow belongs to all of us, is part of us, reflective of our sense of ourselves and of the land from which it emerges. The very human facility of incorporating story into our realm of understanding allows us to enhance this view with certain intangible qualities that add dimension to the idea. We can add spiritual aspects to physical things. We can imply unseen forces to visible phenomena. We can put god into the machine. And, it has to be said, we can take god out again if it suits. With regard to pounamu we can observe these transitions from the physical to the metaphysical and back again. It’s a god stone and a commodity.

Another question seems to arise in realtion to this particular topic of discussion and that is, can I acquire greenstone for myself? Can I buy a piece of pounamu just for me? It’s a widely held ‘belief’ in Aotearoa that you should only acquire greenstone in order to make it a gift. If we covet it for ourselves, bad luck will surely follow. It’s a lovely sentiment with a slightly sinister flip side. Of course, if it were true, it would put the commerce of pounamu in something of an awkward position. And let’s not be shy about it, pounamu has commercial value. It’s a semiprecious stone, it’s nephrite, it’s jade, it’s beautiful, enigmatic, mysterious. In the hands of an Artisan its value multiplies. What are we to make of this apparent conundrum?

I think we can accept that our modern day views, opinions and beliefs regarding pounamu emanates from Te Ao Māori - the Māori World - and the tikanga thereof, which are the practices and traditions that attend the stone itself. We’ve already seen in previous discussions the pre- eminent position of pounamu in Māori life. In Maori material culture, you’d have to say that pounamu was very much the gold standard. It’s important to keep this in mind when we consider that the culture encountered by Captain Cook and to a lesser extent, Abel Tasman, was mercantile, though Tasman didn’t hang around long enough to discover that. But Māori have always liked a good trade, a deal where both sides think they got the better. Trade means transaction and

engagement with others. Trade means communication of ideas and practices. Trade is outward looking. It seeks alliance and arrangement in lieu of conflict. And of course, trade seeks goods. Pounamu as a commodity was not alien to Māori. Pounamu as a source of material wealth was a given. So Pounamu with all its qualities both physical AND spiritual, was immensely valuable. Ngāi Tahu understood this, conquering West Coast hapu to secure the resource and establishing trade routes and workshops to generate and guarantee supply. Te Rauparaha of Ngāti Toa understood this as well when he sought to wrest control of Te Waipounamu South Island from Ngāi Tahu and secure the resource for his own. Such is the mana of the stone that wars are fought for it. When Pākeha took a shine to the stone, another layer of value was added as pounamu went international and the world would come to know greenstone from New Zealand. But economic value is only ever part of the equation, unless you’re a neoliberal. Thankfully I’m not here to argue economic theory. I’m here to discuss the other gods in the room.

As mentioned throughout this series of blogs, pounamu has great mana. Mana emanates from whakapapa. Whakapapa ties us to each other and to all things. Mana resides with tapu. People and things of great mana, great spiritual force, also have about them a tapu, or sacred aspect. Mana and tapu are metaphysical concepts. The metaphysical realm is a familiar place in Te Ao Māori. Mana, Tapu, Noa, Mauri, Wairua, Atua… these are all spiritual concepts that coexist easily within and beside the physical Māori world. Human activities and endeavours come laden with measures of mana, tapu and noa. Tapu is a sacred or holy or sanctified state subject to the direction of certain Atua, which you might call gods; Noa can be seen as the state that exists when tapu is removed. Some things are so charged with tapu, that an individual’s wairua, or spirit, might be effected, to their detriment. Activities such as warfare and tangihanga are among the most tapu. These activities deal with death. Tōhunga are tapu. Tōhunga possess sacred, often esoteric knowledge. They are specialists in their field. Their knowledge and skills carry tapu. Whakairo - the

art of carving - is a Tapu pursuit. The Tōhunga whakairo has the wānanga - the knowledge of appropriate ritual and practice that is the tikanga of carving, so the Tōhunga whakairo is a person of great mana and tapu You can see then that individuals associated with these types of activities will also possess mana and tapu. In a sense it takes great mana to handle great and potent tapu. So certain rituals evolved to secure this relationship of mana, tapu and noa, to ensure proper conduct and a safe pursuit.

art of carving - is a Tapu pursuit. The Tōhunga whakairo has the wānanga - the knowledge of appropriate ritual and practice that is the tikanga of carving, so the Tōhunga whakairo is a person of great mana and tapu You can see then that individuals associated with these types of activities will also possess mana and tapu. In a sense it takes great mana to handle great and potent tapu. So certain rituals evolved to secure this relationship of mana, tapu and noa, to ensure proper conduct and a safe pursuit.

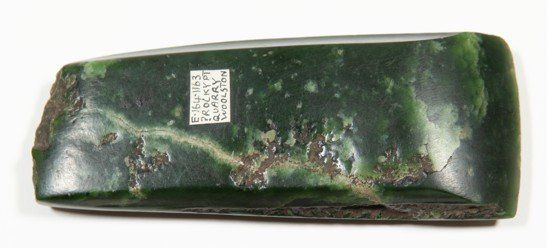

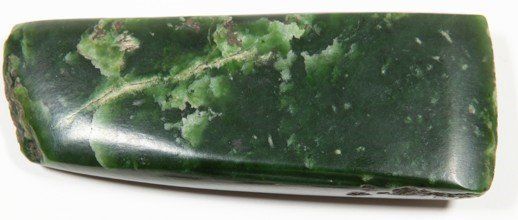

A toki pounamu for example, fashioned by a tōhunga whakairo - an expert carver - for use in the construction of a waka taua - a vessel of war - will be a tool of great mana, great tapu. As such, it must be blessed - whakatapu - with ritual karakia and ceremony. Karakia we might think of as a kind of prayer, an incantation invoking the appropriate god or gods to the task at hand. Pounamu, as we have seen in earlier blogs, comes already latent with mana and tapu so it requires extra special treatment. A mere pounamu - a weapon of war will require similar special consideration, special blessing. A heitiki that once was a toki and now is an heirloom requires the the same sense of ritual, if only as a private karakia by the giver, so adding to its mana and becoming more sacred with every generation of existence. Whakatapu. Which brings us once again to the question of whether or not to bless the stone, and the bigger question; ‘What do I believe?’ If I believe that mana, tapu, noa, wairua, atua and all the other spiritual aspects are as real as the stars that are there in the sky in the daytime, then I will bless the stone…

November 2020

Ben Brown

November 2020

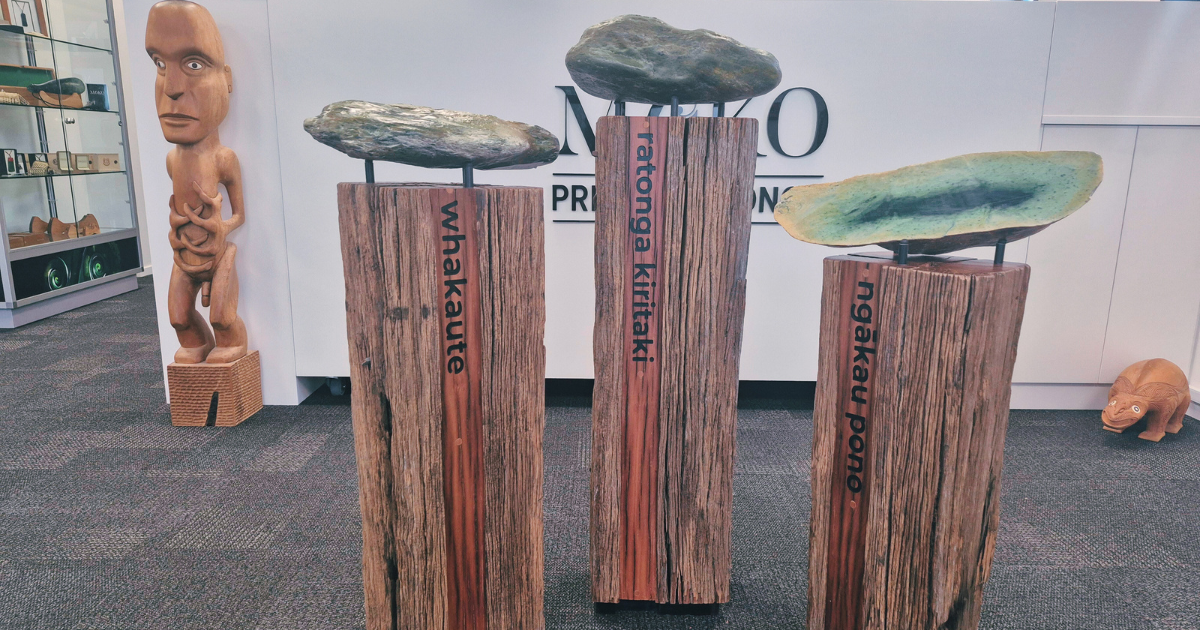

Moko Pounamu Knowledge Library

We believe that gifting pounamu is a profound act, one that deserves to be supported by deep knowledge, genuine care, and absolute integrity. This belief is the foundation of our business, which is built on three core pillars that guide every interaction, both in our Christchurch shop and across the globe.