WELLBEING AND WATER

n Te Ao Māori - the Māori World - particularly in pre- European times, the health and wellbeing of an individual might be regarded as an indication of the state of that person’s engagement or relationship with their immediate environment or the wider world around

them. Illnesses and ailments could be seen as a clear sign of some imbalance between the whole of the individual, that is the emotional/physical/spiritual self and the physical/spiritual realms wherein he or she exists on a day-to-day basis.

Perceiving the causes of these imbalances and rectifying or correcting appropriately according to context and circumstance falls to the tohunga, the specialist in such matters where Rongoa - traditional Māori healing practice - is called upon in times of need. Rongoa tikanga uses a combination of plant based remedies, karakia, blessing and cleansing rituals, and what we might recognise today as forms of ‘counselling’ to treat and hopefully resolve these imbalances, sometimes calling on or delving into whānaungatanga - familial relationships and/or whakapapa - ancestry and heritage aspects to fully explore every conceivable perspective regarding causal and curative possibilities.

In simple terms, if you’re sick, something is out of whack between you and the world in which you live. Maybe the fish you had for dinner was off, or deep down you’re still upset at

Aunty’s passing because you didn’t get to say goodbye, or you just can’t find your late Mum’s pounamu pendant anywhere and you’re beside yourself with grief. These are three of the many examples I’ve witnessed myself over the years where the tohunga was called instead of the doctor, but tikanga proved as effective when applied appropriately, with knowledge and compassion.

Bad fish might be attended to by certain herbal remedies, appropriate cleansing and perhaps a karakia to Tangaroa just to be on the safe side. Aunty’s passing will require a measured and delicate approach with an esoteric understanding of particular tikanga and karakia, a deep awareness of the nature of tapu and noa, and an intimate knowledge of Te Pō with more than just a passing acquaintance with the dead. As for your late Mum’s pounamu though, time will temper the grief, but the weight of such a loss will remain heavy in the heart so long as the taonga remains lost. And as with many an heirloom piece, the tapu that attends it has been magnified through generations of whānau and whakapapa manifesting a spiritually charged context that must be navigated carefully for the well being of everyone involved.

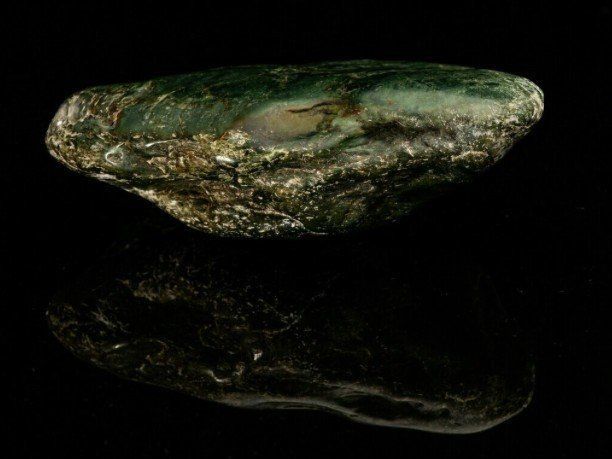

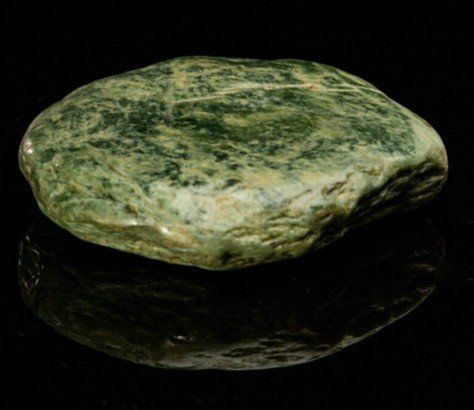

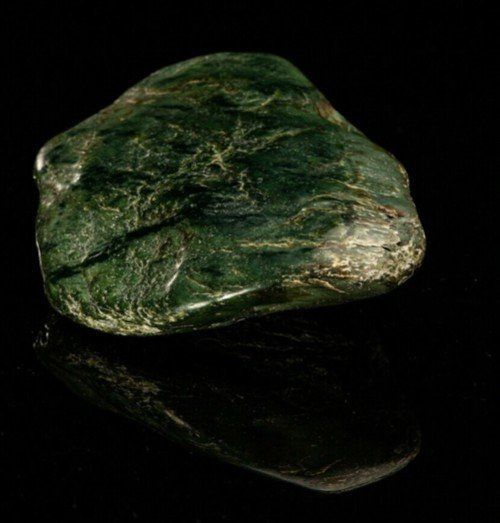

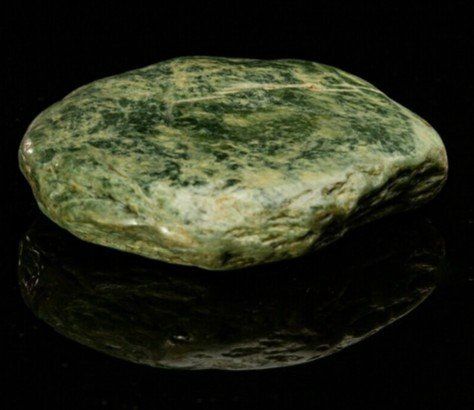

Traditionally, pounamu is not generally associated with Rongoa practice though clearly there are spiritual associations with greenstone that speak to a sense of security and well being, of peaceful and harmonious relationships, of being in accord with things. I’ve referred in previous blogs to the empathic nature of pounamu, how it seems to have the capacity to imbue itself with the energies around it, to take on the

warmth of its wearer for example. But also to absorb the bad with the good. Which means there will be times when pounamu requires very careful and specific handling. Tapu and noa need careful attention. Balance is key to maintaining the calmness of spirit that wellness requires.

But Māori are not the only people to perceive the mana - the spiritual energies and properties - that emanate from pounamu. New age techniques and practices based on often ancient indigenous traditions of energy healing cite pounamu and jade as variously a heart stone, a healing ‘crystal’ beneficial to heart and lungs, or indeed a healing stone of sufficient energy to heal all ‘chakras’ - the spiritual energy centres of the human body - of which there are anything from seven to over one hundred, depending upon which belief system you adhere to.

I’m completely open to the idea of the human body as a kind of dynamo or generator of many different energies, from the electromagnetic interactions and forces at play in our atoms, to the chemical processes expending and releasing energy in our muscles and organs, to the heat and mystery of our livers to the toxic acidity of our stomachs to the 100 watts of power our body’s produce at rest by the simple expedient of cells powering up to maintain lines of communication

I’m completely open to the idea of the human body as a kind of dynamo or generator of many different energies, from the electromagnetic interactions and forces at play in our atoms, to the chemical processes expending and releasing energy in our muscles and organs, to the heat and mystery of our livers to the toxic acidity of our stomachs to the 100 watts of power our body’s produce at rest by the simple expedient of cells powering up to maintain lines of communication

with each other and with ‘mission control’ i.e. the brain, which itself generates around

12 - 24 watts of power as it goes about an average days business of running a body, directing a life and trying not to get carried away with its thinking processes, so the idea of ‘energy centres’ spread around the body or situated along energy ‘meridians’ isn’t of itself an outlandish notion.

‘Spiritu

al’ energy is a concept I find a little harder to pin down, although having said that, Māori concepts such as Tapu, Mana, Wairua, Mauri, Ihi, and Wehi allow me to readily entertain the possibility of at least six different ‘types’ of such energy right here, right now. The Māori world view also allows these energies to exist outside of a human source or emanation so that we can detect tapu and mana, mauri and wairua, ihi and wehi throughout the natural world as well. Rivers and mountains, rocks and trees, even phenomena like winds or lightning or rainbows, or transient states such as mist or cloud are known to manifest such energies.

We know already that pounamu occupies a spiritually charged position or status. Sometimes that’s a blessing. As often as not, it’s grief. But the most ubiquitous of these sources of energy gets plundered hard out every day for both its spiritual and physical energy qualities as well as its universally acknowledged healing properties. We’ve pillaged, sacked and squandered the stuff since time immemorial and will continue to do so across every culture in every land wherever humans care to tread because without it, we’re all as dead as dust.

We know already that pounamu occupies a spiritually charged position or status. Sometimes that’s a blessing. As often as not, it’s grief. But the most ubiquitous of these sources of energy gets plundered hard out every day for both its spiritual and physical energy qualities as well as its universally acknowledged healing properties. We’ve pillaged, sacked and squandered the stuff since time immemorial and will continue to do so across every culture in every land wherever humans care to tread because without it, we’re all as dead as dust.

Maori have always acknowledged the existence of this energy source in the most intimate, yet subtle way imaginable. We ask any other human we come across that we don’t already know, one simple question; Ko wai koe? - Who are you? It’s a kind of riddle, meant as a gentle reminder of the proper way of things, or in other words, tikanga. But just about everyone gets it wrong. They will inevitably answer Ko Bill au or Ko Betty au. You know, I’m Bill or I’m Betty. No No No!

Look… If I ever ask you that question, Ko wai koe? like, Who are you? This is what you say, ok? You say this - Ko wai au? Like, ‘What - Who am I?’ Then YOU pause for a second or two before continuing Ha! Ko wai au! Say Exactly the same thing! But the intonation should assert not enquire. Make a statement, don’t ask a question. As a statement the phrase says: I AM WATER! Ko wai au!

Look… If I ever ask you that question, Ko wai koe? like, Who are you? This is what you say, ok? You say this - Ko wai au? Like, ‘What - Who am I?’ Then YOU pause for a second or two before continuing Ha! Ko wai au! Say Exactly the same thing! But the intonation should assert not enquire. Make a statement, don’t ask a question. As a statement the phrase says: I AM WATER! Ko wai au!

As water we exist as part of every other thing that yields from the source as well. And so, as part of the pounamu, we can draw strength and durability from the stone, from its attributes and character, yet we cannot sustain and renew ourselves.

We must then attend to what remains of our mana with resolve and acceptance, and imagine instead our small forgotten river as a last and secret tributary spilling only the deep and pure light of majestic and immortal consequence, cascading thunderous through towering ravines of origin where first the Wai Pounamu - the greenstone waters - flowed before there was even a minor stone of any poor hue or a mumbled and hesitant legend to give either Gods or grace.

Ben Brown June 2021

We must then attend to what remains of our mana with resolve and acceptance, and imagine instead our small forgotten river as a last and secret tributary spilling only the deep and pure light of majestic and immortal consequence, cascading thunderous through towering ravines of origin where first the Wai Pounamu - the greenstone waters - flowed before there was even a minor stone of any poor hue or a mumbled and hesitant legend to give either Gods or grace.

Ben Brown June 2021

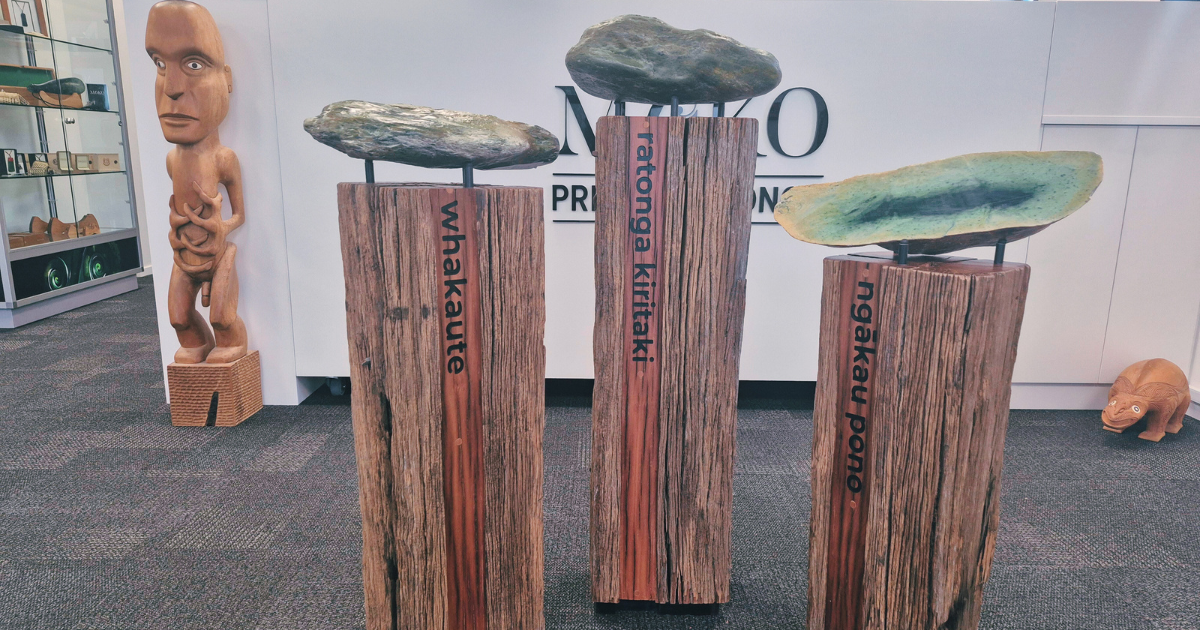

Moko Pounamu Knowledge Library

We believe that gifting pounamu is a profound act, one that deserves to be supported by deep knowledge, genuine care, and absolute integrity. This belief is the foundation of our business, which is built on three core pillars that guide every interaction, both in our Christchurch shop and across the globe.