FREE SHIPPING ON ORDERS OVER $100 WITHIN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA

-

Home

- Shop ▾

- Learn ▾

-

Contact us

-

Sale

Wāhanga Tuatoru: Chapter three by Ben Brown

The story of stone is the story of ages and origins.

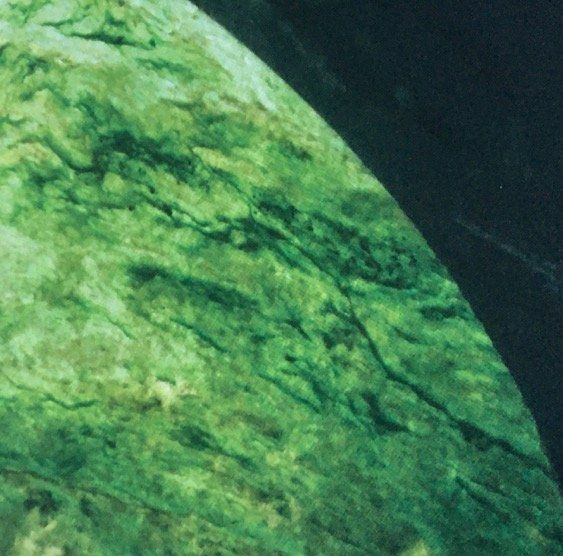

Stories emerge from this impulse; mythologies and traditions, folklores and philosophies, tall tales and seemingly immutable truth that built our understanding, our cosmologies, made sense of things so that each generation knows a little bit more than the last or at least, would like to think so. Yet here we sit on Sagan’s small blue dot, this convenient rock hurtling through the universe, with hundreds of thousands of years of accumulated knowledge encoded somewhere within us; in our DNA or our souls depending upon your particular god, and still we are drawn to the mystery and beauty of stone. Greenstone, nephrite jade, bowenite, serpentine. All of it referenced as Pounamu at one time or another, but no less equally cherished.

I’m given to wonder; is it strange that science, mythology, history and anthropology are somehow able to merge at times in an uncanny coalescence of meaning, or is it merely human? We humans after all, invented meaning. Things can be whatever we want them to be. It’s one of our beautifully rendered truths that occasionally gets us into trouble because sometimes nature disagrees. Sometimes however, nature concurs, and what is revealed in those magical moments leaves us a little bit better off than we were. Stone does not lie. Stone is honest as a mountain. Stone is humble and immense.

There are stories from our first days on these

islands, when we were no more than tangata

and wahine and whānau and small hapu,

moving from river mouth to mountain to plains,

exploring, discovering, living and dying and

building tradition. The stories tell of Pounamu as

a fish who swam here from the ancient land of

ancestry, or down from the heavens, or up from

deep within the earth that is Papatuānuku, the

mother to us all.

We saw mana and wairua and great mauri in

this fish that was a stone. We made treasures

and tools and implements of death and authority

from it, and in so doing the stone taught us the

nature of the land from which it came. Some

stories say that Pounamu is a taniwha, a mythical creature of great and magical power, while others say the stone is a woman taken from her lover. She hides now, lost as a captive in the rivers, waiting for him to come to her rescue.

These are origin stories that sought to

explain our relationship to the world around

us; to the providence of the earth and the

rivers and the obligations upon us to sustain,

protect and ensure the resource.

In 2015 new geological research into ‘the

movement of pounamu’ found that

greenstone moves ‘in a river like fish

swimming upstream.’ Extended surveys of

West Coast rivers, close analysis of

geological maps and novel experiments to

study the movement of rocks in water flow

was carried out by GNS Science in conjunction with South Island owners of pounamu, Te Iwi ō Ngāi Tahu, in an effort to better understand the travelling habits of this enigmatic stone. Principal geologist Dr Simon Cox said pounamu was unlike any other mineral because it was always on the move.

‘There is pounamu in hard rock occurrences, and in small slivers in mountain reefs, but most Pounamu is found in the river bed. . . Unlike any other mineral resource, it gets moved in floods and buried and exposed, so there’s the old lore that you look for pounamu after a storm. . . Pounamu is harder and more dense than other rocks, and the other rocks break down while the pounamu tries to hang in there and stay in the rivers. . . It’s a bit more like fish swimming up into the current and trying to stay where they are: they swim upstream moving backwards and forwards.’ Always did wonder why mum used to tell me pounamu gets homesick.

Poutini is the Taniwha. He is te kaitiaki o te

pounamu, the guardian of the greenstone. He

protects his rivers with jealousy, trapped by his

desires to the task of guarding a love he cannot

have. His mauri, his life essence, is pounamu but

this is only part of what binds him to the western

shore where the rivers disgorge.

There is a woman, her name is Waitaiki and

Poutini has taken her for his own, and yet she will

not yield. The taniwha cannot bear it. He turns her

into pounamu and places her in a deep pool near

the headwaters of a river whose mouth he guards

relentlessly, despairingly, for ever.

We can regard the story, or stories more correctly, of Poutini as Aotearoa New Zealand’s first geological survey. The taniwha of greenstone enters our raditions in various guises; as a fish, as a stone, as a mythical, magical creature, alone or in company. He is even a star according to some ancient lore. Whether from Hawaiki the ancient homeland or Te Moana Kura, a sacred sea or even the heavens; Poutini’s journey carries wānanga - deep knowledge - of our realtionship to the land, sea and rivers and more importantly, to the rocks and stones of utility and beauty and deadly efficiency that helped ngā iwi Māori - the Māori people - establish here beneath the long white cloud. Poutini’s arrival reveals to us the tools of

settlement.

Ngāi Tahu tradition holds that Poutini was pursued here to Aotearoa by another taniwha, Waitipū, who is the guardian of Hinehōaka (called Hine-tū-a-hōanga in other traditions); she whose essence is sandstone, blades of which are used to cut, abrade and score the pounamu that is Poutini. So you see that they are natural enemies, and the science of geology works its way into legend. Poutini also occupies that space in our cultural memory that is inhabited by deities and humans together. So we see that when he pauses in his escape from Waitipū at an Island called Tūpua,

which is known today by another name - Mayor Island in the Bay of Plenty, north off the coast from Tauranga, he is drawn to the beauty of a woman bathing near the island shore. She is Waitaiki, the wife of a great warrior chief of the island, Tamāhua. Tūpua is what we know of as obsidian, the black volcanic glass for which the island, an ancient volcano, is named. The tūpua is highly prized as both a tool and a weapon and there is a plentiful supply on the island. So another geological reference is framed in Poutini’s story. But for now, Poutini only has eyes for Waitaiki and so he must have her for his own. Seized by his passion he sweeps her away. In this version of events Poutini now has two problems. The taniwha Waitipū, who serves Hinehōaka of the Sandstone, still seeks him out. And Tamāhua, upon learning of his wife’s disappearance, now vows to find her and punish whoever is responsible. Poutini has no choice but to flee, taking his captive with him.

Some accounts tell us he fled first to the shore of nearest convenience, to Tahanga on the Coromandel Peninsula, where basalt would be quarried for the making of adzes, and then overland to Taupo and a bay in the great lake called Whangamatā, named for the more common kind of obsidian, matā, which is known to be plentiful there. These were the razor sharp disposable blades of the day. Southward then to Rangitoto (D’Urville Island) just off the north coast of South Island, to Whangamoa, a high hill range to the east of Whakatū (Nelson). Both of these places would prove a rich source of argillite, or pākohe, a strong, hard stone that could hold an edge but could be worked with granite hammer stones and even fire. Pākohe is particularly associated with the Nelson/Marlborough area but is known to have been traded to all parts of Aotearoa for its general utility. Over the first few hundred years of settlement, pākohe would prove itself the bedrock of foundation.

From the high hills above Nelson, Poutini, with his captive, continued on without delay. Relentless and deadly pursuit harried him, barely a day away. To Onetāhua - Farewell Spit, where stones of useful and convenient variety, shape and size are found washed up there, including argillite and serpentine, having begun a journey countless millennia ago from the mineral belts in the mountains surrounding Golden and Tasman Bays. From there down the west coast of South Island,

pausing briefly at Pāhua near Punakaiki, until a

feeling of dread forced Poutini away.

His dread is not unfounded. Embedded in the limestone at Pāhua is the flint that enabled the people to first bore holes through pounamu. (see Wāhanga Tuatahi; Chapter One), Tamāhua still follows, determined and implacable, aided by his magic, driven by his love. And somewhere out there ,Waitipū, the sandstone Taniwha, grimly anticipates the grinding of his enemy. Poutini cannot run forever. All the while Waitaiki laments, grieving for her home and her lover.

But Poutini’s flight is coming to an end. Waitaiki is cold, bereft, tired, withdrawn. In his desperation, the taniwha removes from the sea at the mouth of the Arahura river, heading upstream with his captive to find some secretive place of concealment. Tamāhua continues south along the coast past the point of the taniwha’s diversion and on until he reaches Takiwai at Piopiotahi, the mouth of Milford Sound, where his magic tells him that Poutini has, for the moment, eluded him. Tamāhua turns and heads back up the coast, careful now to attend his magic, which eventually reveals the Arahura river as the site of both his desire and his retribution. The matter is coming to a head. Poutini knows this. Waitaiki too, senses an end to her misfortunes. The Taniwha is desperate. Waitaiki stands, now resolute in her defiance. Tamāhua draws ever nearer. Spite overwhelms Poutini. If he can’t have this beauty from the north, nobody can. Wielding a magic of his own, he transforms Waitaiki into his own essence - pounamu - and places her in a deep pool near the headwaters of the river. Using all of his skills of deception then, he quietly slips away downstream hidden in the turbulence and shadows of the river, unseen by Tamāhua who is perhaps distracted by his certainty that Waitaiki is somewhere close at hand. Soon Poutini is back at sea, where he remains to this day, according to this tradition, giving his name to that part of the western shore that is called Te Tai ā Poutini. Tamāhua will find his beloved Waitaiki and some say his lament might still be heard in that part of Aotearoa, echoing through the valleys and hills as a tangi to announce his grief. Waitiki is remembered as the mother lode of pounamu.

To imagine however that this is the only tradition pertaining to pounamu, regarded as the most valuable material resource in a land where tribal

society competes for prominence, space and all other resources, would be to completely misunderstand the place this remarkable stone holds in

the heart of the people. There are more traditions and variations of the story than there are types of pounamu itself. Many more. There are even mythologies that tie the greenstone to the very separation of earth and sky, placing it in the hands of Gods at the beginning of the first lighted day in the guise of the legendary toki, Te Awhiorangi, used by Tāne to slash the vines binding Rangi and Papa together.

The stories surrounding Ngāhue for example, called Ngake in some places, reveal to us the complexities involved in unravelling the apparent mystery of pounamu. Poutini is once again present although, his role will vary depending upon whom is telling the story. Some say the taniwha is under Ngāhue’s charge and travels with him as a companion on his way to Aotearoa. Others insist that Poutini obeys Ngāhue’s outraged wife who sends the taniwha on a mission to destroy her errant husband. Still other traditions place Hine-tū-a-hōanga of the sandstone as a jealous antagonist of Ngāhue, intent on destroying Ngāhue’s taniwha, again with her own beast, being envious of Poutini’s qualities.

Regardless, it is Ngāhue who is widely credited with bringing the stone to the attention of the people. Tied in many traditions to the exploration journey of Kupe and his apparent discovery of these islands at the bottom of the vast Polynesian triangle (although there are other traditions that beg to differ with the popular version of events), Ngāhue is a prototypical figure in the evolution of early Maori cultural advancement, and a name to mark the beginnings of settlement and ongoing occupation. He is said to have taken the pounamu back to the ancient homeland of Hawaiki (or in some traditions, Rarotonga or Ra’i’atea) where he carved the first greenstone tiki as well as two adzes - toki - named Tutauru and Hauhauterangi that were used to carve the waka, Tainui and Te Arawa. Here then begins the tradition of working pounamu, which in those times was called te ika a Ngāhue - Ngāhue’s fish.

The Ngāhue traditions begin with pursuit, with a chase from the

The Island of Tūpua is again prominent

in these other versions of the story of

stone as tūpua - the obsidian itself - will

always be important to the people. But

Waitaiki and Tamāhua are absent from

these tellings. Instead it is Ngāhue

attempting to hide Poutini from the

pursuing Hine-tū-a-hōanga and her retinue, first at Tūpua and then, by differing accounts, at various places down the east coast of North Island such as Waiapu on East Cape, Uawa near Tologa Bay, Turanga, Waimata, Nukutaurua, In Hawkes Bay near Heretaunga and further south along the coast of Wairarapa, each time being thwarted by the presence in those places and others of sandstone, chert and other progeny of Hine-tū-a-hōanga, the eternal enemy of pounamu.

Or it is Poutini in pursuit of Ngāhue, to the same effect as far as the purpose of these stories of stone are concerned, that is, to mark in the memories of generations these trails and places of value. That all of these stories, mythologies and traditions, and others not even mentioned here still lead to Arahura by way of obsidian, basalt, argillite, sandstone and flint suggests that Maori tradition had come to some of the same broad conclusions that geological science arrived at many centuries later. The story of stone in Aotearoa is mute if not for pounamu.

landscape of legend and mythology and ancient whakapapa to a new land of rich and wonderful resources. This seems to me to reflect the vast distances and dangers the people were prepared to endure as they travelled the length of these islands to seek out such items of value and utility and enduring importance to trade, to build with, make war with or simply to admire.

The Island of Tūpua is again prominent in these other versions of the story of stone as tūpua - the obsidian itself - will always be important to the people. But Waitaiki and Tamāhua are absent from these tellings. Instead it is Ngāhue attempting to hide Poutini from the pursuing Hine-tū-a-hōanga and her retinue, first at Tūpua and then, by differing accounts, at various places down the east coast of North Island such as Waiapu on East Cape, Uawa near Tologa Bay, Turanga, Waimata, Nukutaurua, In Hawkes Bay near Heretaunga and further south along the coast of Wairarapa, each time being thwarted by the presence in those places and others of sandstone, chert and other progeny of Hine-tū-a-hōanga, the eternal enemy of pounamu.

Or it is Poutini in pursuit of Ngāhue, to the same effect as far as the purpose of these stories of stone are concerned, that is, to mark in the memories of generations these trails and places of value. That all of these stories, mythologies and traditions, and others not even mentioned here still lead to Arahura by way of obsidian, basalt, argillite, sandstone and flint suggests that Maori tradition had come to some of the same broad conclusions that geological science arrived at many centuries later. The story of stone in Aotearoa is mute if not for pounamu.

Glossary:

Hapu: Tribal grouping of related whānau, sometimes called a sub-tribe.

Pregnant.

Mauri: A spiritual essence or life force.

Tangata: Man.

Tangi: Lament. Call.

Taniwha: Mythical creature. Supernatural being. Metaphorical form for greatness or mana in an individual.

Tiki: Stylised human figure, known as heitiki when worn as a pendant.

Toki: Adze blade or axe.

Wahine: Woman.

Wairua: Spiritual aspect.

Waka: Canoe. Ancestral vessel of voyage and discovery closely tied to whakapapa, or lineage. Whānau: Extended family grouping.

Give birth.

Become a Moko Club Member

Thanks for becoming a Moko Club Member

Oops, there was a slight error when you hit Join.

Please try again after a few minutes.