Victorian Colonial Jewellery & Pounamu

Bracelet from the late 19th century

Māori might have imagined, for a moment or two at least, that they’d signed up for British citizenship in February 1840, with a vague third clause in the treaty at Waitangi representing someone’s ideal (Henry Williams maybe?) of an engagement between the natives and far off Kuini Wikitoria, then not even twenty-one years old and nearly three years into the job of being Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Empress of an Empire - the Sovereign and symbol of the Greatest power in the world.

Born in the mother country back then, to the right station or status, in the right house for instance, to the right lord and lady noblesse oblige notwithstanding, one might reasonably expect a life of particular privilege and advantage, with access to opportunity, education, even liberty if liberty means freedom to choose anything above duty, drudgery, or destitution and dead in the tenements by thirty.

Liberty there must have been, in some allocation at least. A lot of those children of Empire found enough of it to come here. In spite of Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s best efforts to establish a kind of class oriented society built on the notion of ‘sufficient price’ (for land in the first instance), new modes of thinking about social mobility arrived with the aspirations of our settlers and remain stubbornly persistent to this day. Wakefield’s ‘systematic colonisation’ would have kicked off at the top, with a land owning class who, possessed of property, capital and insight, would set about building Utopia with diligence, good judgement and prudent investments in labour and industry, science and the arts, and all would be well in the end.

To be fair, the land owners did have their day, with the great run holders of Canterbury, Hawkes Bay and Wairarapa leaving their mark on the landscape, culture, industry and politics of much of 19th Century New Zealand, traces of which you can still recognise in the shape and manner of things we like to think of today as ‘ours’. Long before dairy herds milked us to riches, sheep cockies showed us the way. But the labourers, scullery maids and crofters from the clearances who came here looking for the dream didn’t go to the run holders homestead to find it. So it is that colonials become New Zealanders.

These new New Zealanders have it in mind to express themselves to the world, to the old world in particular, to show how far you can come, how much you can grow in such a short time. Objects of beauty and adornment allow such expression, wrought from the minerals and labours of the new world, rendered in form, aesthetic and utility from old world ritual, tradition and craft creating for a ‘moment’ in time genuine artefacts of story and place.

A pounamu pendant displaying in gold what seems to be an example of the masonic palm symbol, but with a heart instead of an all-seeing eye (see above), could be a colonial mason’s unique expression of love to a sweetheart, or is it simply a way of saying ‘my heart is in your hands’. Maybe its both, stands to reason it could well be. The piece is dated around 1880 and New Zealand was awash with masons then. Whatever the inspiration, to me there is a naive confidence in the idea of this piece. I mean naive in the nicest possible way, like a genuine innocence. I think the idea is prettier than the piece itself, though its not without a certain charm.

Matters of the Victorian heart gave romance currency with the Queen herself so openly besotted with her German cousin the consort Prince Albert. And rightly so by all accounts if her journals are accurate in their gushing recollections of his courtship, wooing and so forth. These days we can see for ourselves how the public love of royalty does strange things to the masses

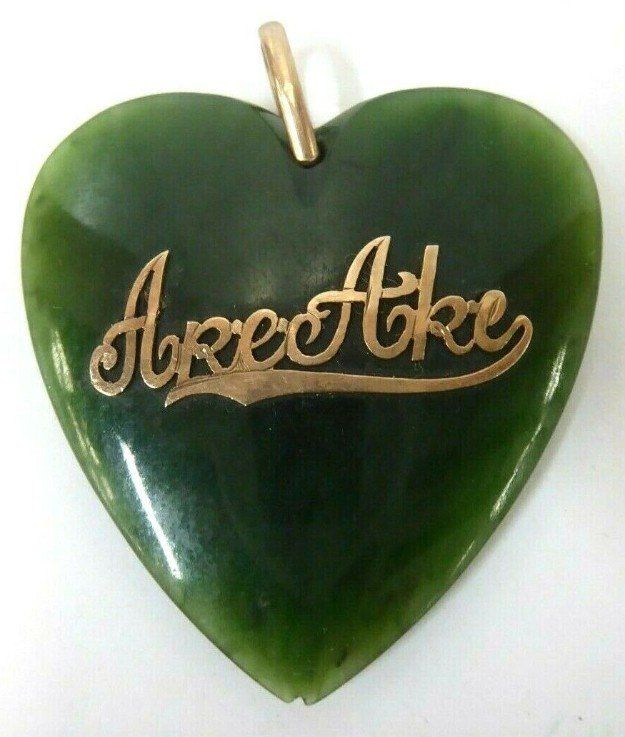

Nonetheless the eternal heart shaped pendant seemed ubiquitous and why not. Pounamu set with gold is a striking liaison with a symmetry about it that makes perfect sense in a West Cosat River like the Taramākau for instance. Sentiments expressed in te reo suggest a certain pride in the exotic association. Ake Ake - Ever and Ever, as popular almost as Kia ora back in the late 1800s

These two items in particular speak to the writer in me, the paper knife with its defiant little hei tiki, and a Victorian page turner so as not to mark or curl the corners of a page as one reads, probably used as a bookmark as well for convenient utility. It’s what I would’ve done with it anyway. I can imagine these items on someone like Alexander Turnbull’s desk in his library surrounded by his beloved books and correspondence. The page turner probably looks like an eccentric or frivolous or even pretentious device through today’s eyes but I don’t know, it shows great regard for books if nothing else and

books are worthy objects in their own right. Books are greater by far than the sum of their parts. Books represent the human journey. They are the record of our existence. Why not treat them with respect. Personally, if I was looking for pretentious frivolity, I’d go no further than a single chopstick.

With neither morsel nor a mouth to serve, what use. . .

Chopstick, square in section c.1890